There is an everlasting conflict, in every city, between the logic of maximising returns and the standards for human life. This conflict is nothing new. Yet for the last thirty years, alternative players have proposed innovative tactics: participatory processes against top-down decision making, transversal thinking against segmented disciplinary approaches, illegal or temporary occupation against speculative development… These movements attract idealist architects fresh out of school, who use them as a platform to imagine new paths for urban life. Alas, the odds aren’t in the idealists’ favour. As dominant forms of city-building leverage the vast array of industrial methods, they still hold a decisive advantage through one central tool: profit-making.

As it turns out, profit is an incredibly efficient method for social coordination. At scale, one could argue it’s the only efficient one. Money, as a universal medium of exchange, helps align the interests of a vast coalition of diverse players. And as a clear unit of account, it allows for a single, crystal-clear criteria to launch or manage any project. In other words: profit-making is both a unifying goal and a universal metric. By contrast, alternative approaches seem to lack such a weapon. How do you effectively measure the quality of a project beyond its cost-to-revenue ratio? By their very nature, qualitative practices are hard to quantify, which makes their impact harder to communicate, and their work harder to organize at scale.

Since the 1990s, a series of indicators have been proposed to document the “impact” of project development through a range of indicators, such as long-term job creation, quality of life, clean water availability or biodiversity. Though effective, these “impact metrics” are fundamentally flawed. By relying on costly studies, only implemented once the project is under way, impact measurements always come last and are mostly useful to market a project locally. In our experience, they are almost never the decisive criteria for launching a project.

In the business world, these indicators are referred to as “vanity metrics” — numbers that make a project manager proud, but serve no strategic purposes. In other words, they are communication tools — not operational criteria.

To develop metrics tailored for alternative approaches, it is necessary to remember this fundamental challenge: a metric is only as good as the priority it serves. Traditionally, business indicators are each assigned a specific objective, such as productivity, waste reduction or speed, each helping to align teams towards a common goal. In practice, successful strategies often emphasize a single goal, monitored through a single indicator. Take customer satisfaction: at the start of e-commerce, clients were reluctant to buy products they couldn’t try. Some startups understood that satisfaction had to be prioritized over all else — including short-term returns. As they channelled most of their resources to their service staff, they transformed satisfaction from a vanity metric (aimed at shareholders) to a critical factor for success. The same should be true of impact measurement: everybody likes the words “popular participation” or “vibrant neighbourhood” on the brochure. But those words do not hold any weight — yet.

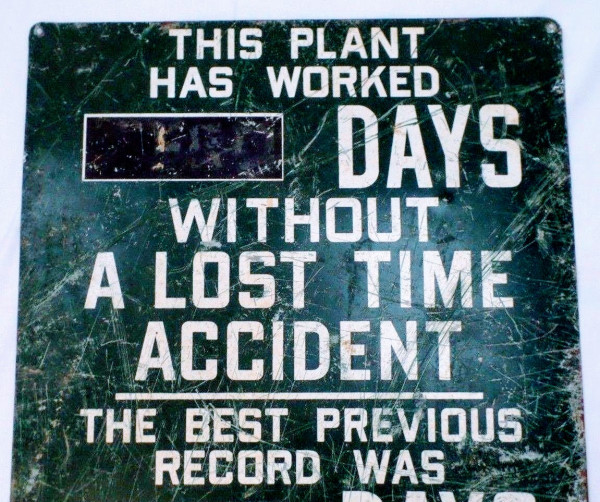

What might an “alternative metric” look like? In its simplest form, it could be as straightforward as the giant clock installed by Tom Hanks in the Fedex office of Cast Away to keep track of time, or the very real “number of days since injury” once displayed in every plant in the US: a number on a board, helping to shift an organization’s focus towards a new priority.

Consider real estate operations, for instance: the size of commercial projects being usually synonymous with the volume of materials used, traditional systems of remuneration — such as paying architects on a percentage of the costs — tend to favour bigger, more wasteful projects. Rotor, a cooperative design practice, has proposed an “hour-per-ton”-metric, to support a shift in priorities, from volume to environmental impact. By comparing a project’s footprint with the hours spent on conception, the indicator could help balance the additional work required of developers and architects with the value created by the reuse of materials, and the adaptation to local needs.

Alternative approaches to city building are currently stuck in a dilemma imposed by their adversaries, between quality and profitability. Yet the question of profitability is entirely dependent on the way we measure value. As in the case of workers’ safety, which proved to be ultimately beneficial to the industrial world, the battle to redefine value starts with the proposition of new indicators: a shift of our collective focus, to redefine urban priorities.